Kena Upanishad Beyond the Known and the Unknown (90 min talk). Swami Swarupananda, the first president of the Advaita Ashrama, Mayavati, and late editor of the Prabuddha Bharata, compiled the present edition of the Bhagavad-Gita with the collaboration of his brother Sannyasins at Mayavati, and some of the Western disciples of Swami Vivekananda.

←Home/ Complete-Works/ Volume 4/ Lecturesand Discourses / →

THOUGHTS ON THE GITA

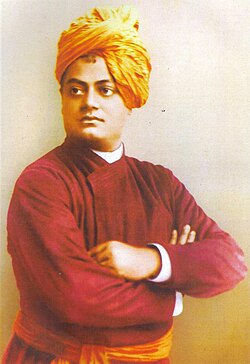

During his sojourn in Calcutta in 1897, Swami Vivekananda usedto stay for the most part at the Math, the headquarters of theRamakrisnna Mission, located then at Alambazar. During this timeseveral young men, who had been preparing themselves for some timepreviously, gathered round him and took the vows of Brahmacharya andSannyâsa, and Swamiji began to train them for future work, by holdingclasses on the Gitâ and Vedanta, and initiating them into the practicesof meditation. In one of these classes he talked eloquently in Bengalion the Gita. The following is the translation of the summary of thediscourse as it was entered in the Math diary:

The book known as the Gita forms a part of the Mahâbhârata. Tounderstand the Gita properly, several things are very important toknow. First, whether it formed a part of the Mahabharata, i.e. whetherthe authorship attributed to Veda-Vyâsa was true, or if it was merelyinterpolated within the great epic; secondly, whether there was anyhistorical personality of the name of Krishna; thirdly, whether thegreat war of Kurukshetra as mentioned in the Gita actually took place;and fourthly, whether Arjuna and others were real historical persons.

Now in the first place, let us see what grounds there are forsuch inquiry. We know that there were many who went by the name ofVeda-Vyasa; and among them who was the real author of the Gita — theBâdarâyana Vyasa or Dvaipâyana Vyasa? 'Vyasa' was only a title. Anyonewho composed a new Purâna was known by the name of Vyasa, like the wordVikramâditya, which was also a general name. Another point is, thebook, Gita, had not been much known to the generality of people beforeShankarâchârya made it famous by writing his greatcommentary on it. Long before that, there was current, according tomany, the commentary on it by Bodhâyana. If this could be proved, itwould go a long way, no doubt, to establish the antiquity of the Gitaand the authorship of Vyasa. But the Bodhayana Bhâshya on the VedântaSutras — from which Râmânuja compiled his Shri-Bhâshya,which Shankaracharya mentions and even quotes in part here and there inhis own commentary, and which was so greatly discussed by the SwamiDayânanda — not a copy even of that Bodhayana Bhashya could I findwhile travelling throughout India. It is said that even Ramanujacompiled his Bhashya from a worm-eaten manuscript which he happened tofind. When even this great Bodhayana Bhashya on the Vedanta-Sutrasis so much enshrouded in the darkness of uncertainty, it is simplyuseless to try to establish the existence of the Bodhayana Bhashya onthe Gita. Some infer that Shankaracharya was the author of the Gita,and that it was he who foisted it into the body of the Mahabharata.

Then as to the second point in question, much doubt existsabout the personality of Krishna. In one place in the ChhândogyaUpanishad we find mention of Krishna, the son of Devaki, who receivedspiritual instructions from one Ghora, a Yogi. In the Mahabharata,Krishna is the king of Dwârakâ; and in the Vishnu Purânawe find a description of Krishna playing with the Gopis. Again, in the Bhâgavata,the account of his Râsalilâ is detailed at length. In very ancienttimes in our country there was in vogue an Utsava called Madanotsava(celebration in honour of Cupid). That very thing was transformed intoDola and thrust upon the shoulders of Krishna. Who can be so bold as toassert that the Rasalila and other things connected with him were notsimilarly fastened upon him? In ancient times there was very littletendency in our country to find out truths by historical research. Soany one could say what he thought best without substantiatingit with proper facts and evidence. Another thing: in those ancienttimes there was very little hankering after name and fame in men. So itoften happened that one man composed a book and made it pass current inthe name of his Guru or of someone else. In such cases it is veryhazardous for the investigator of historical facts to get at the truth.In ancient times they had no knowledge whatever of geography;imagination ran riot. And so we meet with such fantastic creations ofthe brain as sweet-ocean, milk-ocean, clarified-butter-ocean,curd-ocean, etc! In the Puranas, we find one living ten thousand years,another a hundred thousand years! But the Vedas say, शतायुर्वैपुरुषः — 'Man lives a hundred years.' Whomshall we follow here? So, to reach a correct conclusion in the case ofKrishna is well-nigh impossible.

It is human nature to build round the real character of agreat man all sorts of imaginary superhuman attributes. As regardsKrishna the same must have happened, but it seems quite probable thathe was a king. Quite probable I say, because in ancient times in ourcountry it was chiefly the kings who exerted themselves most in thepreaching of Brahma-Jnâna. Another point to be especially noted here isthat whoever might have been the author of the Gita, we find itsteachings the same as those in the whole of the Mahabharata. From thiswe can safely infer that in the age of the Mahabharata some great manarose and preached the Brahma-Jnâna in this new garb to the thenexisting society. Another fact comes to the fore that in the oldendays, as one sect after another arose, there also came into existenceand use among them one new scripture or another. It happened, too, thatin the lapse of time both the sect and its scripture died out, or thesect ceased to exist but its scripture remained. Similarly, it wasquite probable that the Gita was the scripture of such a sect which hadembodied its high and noble ideas in this sacred book.

Now to the third point, bearing on the subject of theKurukshetra War, no special evidence in support of it can be adduced.But there is no doubt that there was a war fought between the Kurus andthe Panchâlas. Another thing: how could there be so much discussionabout Jnâna, Bhakti, and Yoga on the battle-field, where the huge armystood in battle array ready to fight, just waiting for the last signal?And was any shorthand writer present there to note down every wordspoken between Krishna and Arjuna, in the din and turmoil of thebattle-field? According to some, this Kurukshetra War is only anallegory. When we sum up its esoteric significance, it means the warwhich is constantly going on within man between the tendencies of goodand evil. This meaning, too, may not be irrational.

About the fourth point, there is enough ground of doubt asregards the historicity of Arjuna and others, and it is this:Shatapatha Brâhmana is a very ancient book. In it are mentionedsomewhere all the names of those who were the performers of theAshvamedha Yajna: but in those places there is not only no mention, butno hint even of the names of Arjuna and others, though it speaks ofJanamejaya, the son of Parikshit who was a grandson of Arjuna. Yet inthe Mahabharata and other books it is stated that Yudhishthira, Arjuna,and others celebrated the Ashvamedha sacrifice.

One thing should be especially remembered here, that there isno connection between these historical researches and our real aim,which is the knowledge that leads to the acquirement of Dharma. Even ifthe historicity of the whole thing is proved to be absolutely falsetoday, it will not in the least be any loss to us. Then what is the useof so much historical research, you may ask. It has its use, because wehave to get at the truth; it will not do for us to remain bound bywrong ideas born of ignorance. In this country people think very littleof the importance of suchinquiries. Many of the sects believe that in order to preach a goodthing which may be beneficial to many, there is no harm in telling anuntruth, if that helps such preaching, or in other words, the endjustifies the means. Hence we find many of our Tantras beginning with,'Mahâdeva said to Pârvati'. But our duty should be to convinceourselves of the truth, to believe in truth only. Such is the power ofsuperstition, or faith in old traditions without inquiry into itstruth, that it keeps men bound hand and foot, so much so, that evenJesus the Christ, Mohammed, and other great men believed in many suchsuperstitions and could not shake them off. You have to keep your eyealways fixed on truth only and shun all superstitions completely.

Now it is for us to see what there is in the Gita. If we studythe Upanishads we notice, in wandering through the mazes of manyirrelevant subjects, the sudden introduction of the discussion of agreat truth, just as in the midst of a huge wilderness a travellerunexpectedly comes across here and there an exquisitely beautiful rose,with its leaves, thorns, roots, all entangled. Compared with that, theGita is like these truths beautifully arranged together in their properplaces — like a fine garland or a bouquet of the choicest flowers. TheUpanishads deal elaborately with Shraddhâ in many places, but hardlymention Bhakti. In the Gita, on the other hand, the subject of Bhaktiis not only again and again dealt with, but in it, the innate spirit ofBhakti has attained its culmination.

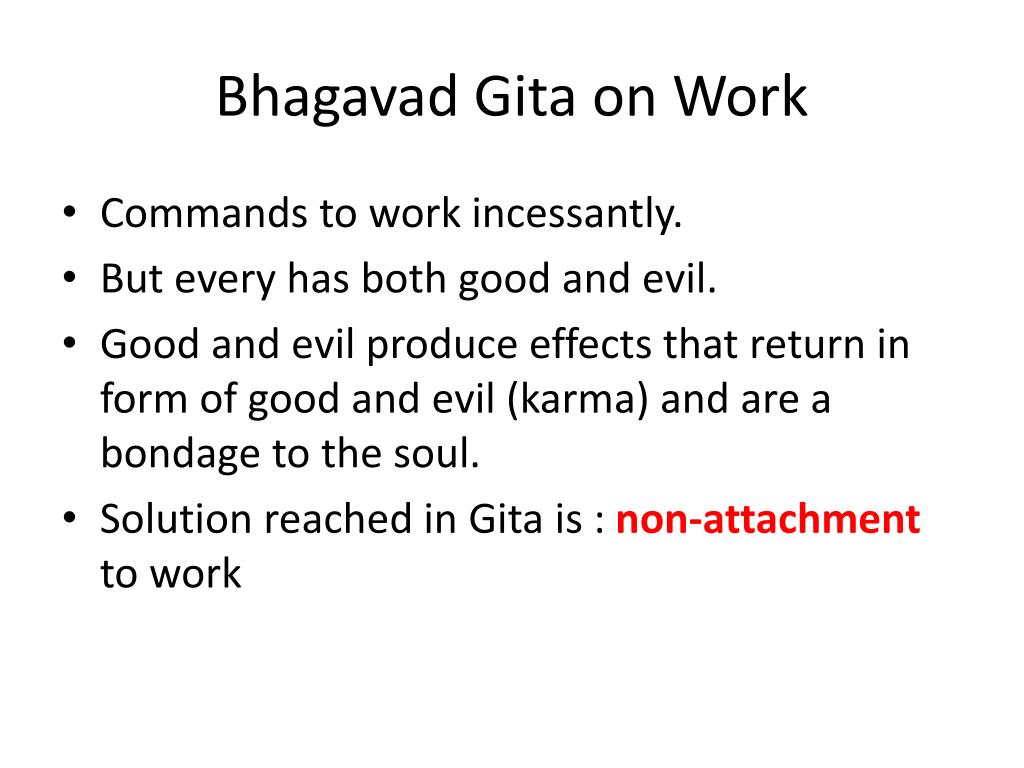

Now let us see some of the main points discussed in the Gita.Wherein lies the originality of the Gita which distinguishes it fromall preceding scriptures? It is this: Though before its advent, Yoga,Jnana, Bhakti, etc. had each its strong adherents, they all quarrelledamong themselves, each claiming superiority for his own chosen path; noone ever tried to seek for reconciliation among these different paths.It was the author of the Gita who forthe first time tried to harmonise these. He took the best from what allthe sects then existing had to offer and threaded them in the Gita. Buteven where Krishna failed to show a complete reconciliation (Samanvaya)among these warring sects, it was fully accomplished by RamakrishnaParamahamsa in this nineteenth century.

The next is, Nishkâma Karma, or work without desire orattachment. People nowadays understand what is meant by this in variousways. Some say what is implied by being unattached is to becomepurposeless. If that were its real meaning, then heartless brutes andthe walls would be the best exponents of the performance of NishkamaKarma. Many others, again, give the example of Janaka, and wishthemselves to be equally recognised as past masters in the practice ofNishkama Karma! Janaka (lit. father) did not acquire that distinctionby bringing forth children, but these people all want to be Janakas,with the sole qualification of being the fathers of a brood ofchildren! No! The true Nishkama Karmi (performer of work withoutdesire) is neither to be like a brute, nor to be inert, nor heartless.He is not Tâmasika but of pure Sattva. His heart is so full of love andsympathy that he can embrace the whole world with his love. The worldat large cannot generally comprehend his all-embracing love andsympathy.

The reconciliation of the different paths of Dharma, and workwithout desire or attachment — these are the two specialcharacteristics of the Gita.

Let us now read a little from the second chapter.

सञ्जय उवाच॥

तं तथा कृपयाविष्टमश्रुपूर्णाकुलेक्षणम् ।

विषीदन्तमिदं वाक्यमुवाच मधुसूदनः ॥१॥

श्रीभगवानुवाच ॥

कुतस्त्वा कश्मलमिदं विषमे समुपस्थितम् ।

अनार्यजुष्टमस्वर्ग्यमकीर्तिकरमर्जुन ॥२॥

क्लैब्यं मा स्म गमः पार्थ नैतत्त्वय्युपपद्यते ।

क्षुद्रं हृदयदौर्बल्यं त्यक्त्वोत्तिष्ठ परंतप ॥३॥

'Sanjaya said:

To him who was thus overwhelmed with pity and sorrowing, andwhose eyes were dimmed with tears, Madhusudana spoke these words.

The Blessed Lord said:

In such a strait, whence comes upon thee, O Arjuna, thisdejection, un-Aryan-like, disgraceful, and contrary to the attainmentof heaven?

Yield not to unmanliness, O son of Prithâ! Ill doth it becomethee. Cast off this mean faint-heartedness and arise, O scorcher ofshine enemies!'

In the Shlokas beginning with तं तथा कृपयाविष्टं, howpoetically, how beautifully, has Arjuna's real position been painted!Then Shri Krishna advises Arjuna; and in the words क्लैब्यं मा स्म गमःपार्थ etc., why is he goading Arjuna tofight? Because it was not that the disinclination of Arjuna to fightarose out of the overwhelming predominance of pure Sattva Guna; it wasall Tamas that brought on this unwillingness. The nature of a man ofSattva Guna is, that he is equally calm in all situations in life —whether it be prosperity or adversity. But Arjuna was afraid, he wasoverwhelmed with pity. That he had the instinct and the inclination tofight is proved by the simple fact that he came to the battle-fieldwith no other purpose than that. Frequently in our lives also suchthings are seen to happen. Many people think they are Sâttvika bynature, but they are really nothing but Tâmasika. Many living in anuncleanly way regard themselves as Paramahamsas! Why? Because theShâstras say that Paramahamsas live like one inert, or mad, or like anunclean spirit. Paramahamsas are compared to children, but here itshould be understood that the comparison is one-sided. The Paramahamsaand the child are not one and non-different. They only appearsimilar, being the two extreme poles, as it were. One has reached to astate beyond Jnana, and the other has not got even an inkling of Jnana.The quickest and the gentlest vibrations of light are both beyond thereach of our ordinary vision; but in the one it is intense heat, and inthe other it may be said to be almost without any heat. So it is withthe opposite qualities of Sattva and Tamas. They seem in some respectsto be the same, no doubt, but there is a world of difference betweenthem. The Tamoguna loves very much to array itself in the garb of theSattva. Here, in Arjuna, the mighty warrior, it has come under theguise of Dayâ (pity).

In order to remove this delusion which had overtaken Arjuna,what did the Bhagavân say? As I always preach that you should not decrya man by calling him a sinner, but that you should draw his attentionto the omnipotent power that is in him, in the same way does theBhagavan speak to Arjuna. नैतत्त्वय्युपपद्यते —'It doth not befit thee!' 'Thou art Atman imperishable, beyond allevil. Having forgotten thy real nature, thou hast, by thinking thyselfa sinner, as one afflicted with bodily evils and mental grief, thouhast made thyself so — this doth not befit thee!' — so says theBhagavan: क्लैब्यं मा स्म गमः पार्थ —Yield not to unmanliness, O son of Pritha. There is in the worldneither sin nor misery, neither disease nor grief; if there is anythingin the world which can be called sin, it is this — 'fear'; know thatany work which brings out the latent power in thee is Punya (virtue);and that which makes thy body and mind weak is, verily, sin. Shake offthis weakness, this faintheartedness!क्लैब्यं मा स्म गमः पार्थ। —Thou art a hero, a Vira; this isunbecoming of thee.'

If you, my sons, can proclaim this message to the world —क्लैब्यं मा स्म गमः पार्थ नैतत्त्वय्युपपद्यते — then all thisdisease, grief, sin, and sorrow will vanish from off theface of the earth in three days. All these ideas of weakness will benowhere. Now it is everywhere — this current of the vibration of fear.Reverse the current: bring in the opposite vibration, and behold themagic transformation! Thou art omnipotent — go, go to the mouth of thecannon, fear not.

Hate not the most abject sinner, fool; not to his exterior.Turn thy gaze inward, where resides the Paramâtman. Proclaim to thewhole world with trumpet voice, 'There is no sin in thee, there is nomisery in thee; thou art the reservoir of omnipotent power. Arise,awake, and manifest the Divinity within!'

If one reads this one Shloka — क्लैब्यं मा स्म गमः पार्थनैतत्त्वय्युपपद्यते । क्षुद्रं हृदयदौर्बल्यं त्यक्त्वोत्तिष्ठ परंतप॥ —one gets all the merits of reading the entire Gita; for inthis one Shloka lies imbedded the whole Message of the Gita.

Bhagavad Gita As Viewed by Swami Vivekananda by Swami Vivekananda

He was a key figure in the introduction of the Indian philosophies of Vedanta and Yoga to the Western world and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing Hinduism to the status of a major world religion during the late 19th century. He was a major force in the revival of Hinduism in India, and contributed to the concept of nationalism in colonial India. Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission. This article was recorded by Ida Ansell in shorthand. To understand the Gita requires its historical background.The Gita part I - Vivekananda - Lectures and Discourses

Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving….

During his sojourn in Calcutta in , Swami Vivekananda used to stay for the most part at the Math, the headquarters of the Ramakrisnna Mission, located then at Alambazar. In one of these classes he talked eloquently in Bengali on the Gita. The following is the translation of the summary of the discourse as it was entered in the Math diary:. To understand the Gita properly, several things are very important to know. First, whether it formed a part of the Mahabharata, i. Now in the first place, let us see what grounds there are for such inquiry.

We haven't found any reviews in the usual places.

the road not taken pdf robert frost

This blog is an honest attempt to answer the above question the best I can

The Bhagavad Gita, often referred to as simply the Gita, is a verse Hindu scripture in Sanskrit that is part of the Hindu epic Mahabharata. The Gita is set in a narrative framework of a dialogue between Pandava prince Arjuna and his guide and charioteer Lord Krishna. The Bhagavad Gita presents a synthesis of the concept of Dharma, theistic bhakti, the yogic ideals of moksha through jnana, bhakti, karma, and Raja Yoga spoken of in the 6th chapter and Samkhya philosophy. Numerous commentaries have been written on the Bhagavad Gita with widely differing views on the essentials. Vedanta commentators read varying relations between Self and Brahman in the text: Advaita Vedanta sees the non-dualism of Atman soul and Brahman as its essence, whereas Bhedabheda and Vishishtadvaita see Atman and Brahman as both different and non-different, and Dvaita sees them as different.

.

Van gogh lust for life bookLectures On Bhagavad Gita By Swami Vivekananda Pdf Lecture

Lectures On Bhagavad Gita By Swami Vivekananda Pdf Lesson

Lectures On Bhagavad Gita By Swami Vivekananda Pdf Download

novel